Substitute teacher crisis forces districts to turn to local businesses and recent grads

In Missouri, a barrel company’s employees serve as substitute teachers. In Connecticut, a superintendent turns to recent high school grads. But solutions to the substitute teacher shortage crisis are elusive in most places as learning losses stack up.

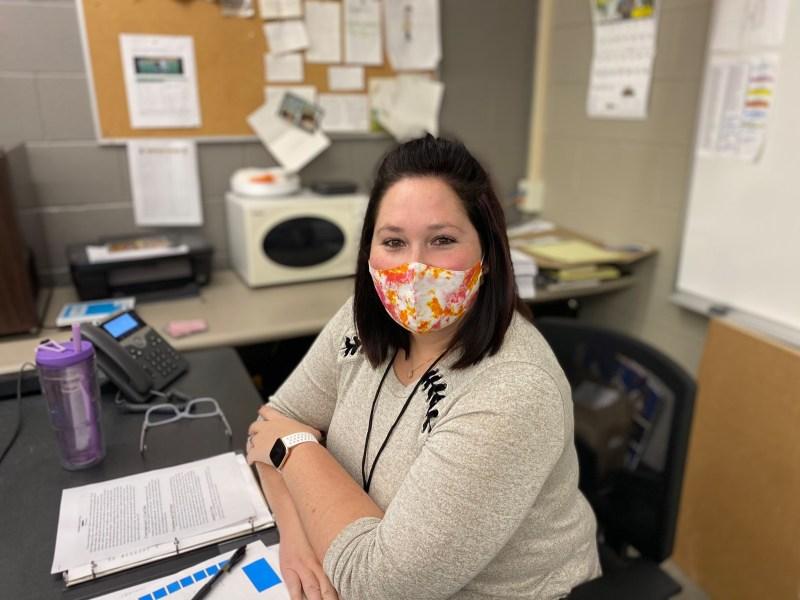

Stefanie Fernandez works for a company that has encouraged its employees to substitute teach in local schools. Armed with a binder of “sub notes,” she’s filling in for an absent teacher in the computer lab at Lebanon (Missouri) Middle School. Credit: Lebanon School District

Stefanie Fernandez usually spends her work week in the finance office of Independent Stave, a company that manufactures oak barrels for bourbon and other spirits, headquartered in Lebanon, Missouri.

But once every week or two since in December, Fernandez has trailed her son into his middle school when she drops him off for classes. She checks in at the office, collects a binder of “sub notes,” and reports to a classroom.

“Good morning, class,” she greets the masked students. “I’m Mrs. Fernandez and this is what we’re going to do today.”

Fernandez is one of several Independent Stave staffers who have taken their employer up on an offer to let them spend up to one day a week substitute teaching in the Lebanon School District. The company makes up the difference between the school district’s substitute teacher pay and their regular salaries.

The goal is to address a substitute teacher crisis that has left districts across the country struggling to find substitutes when teachers are absent because of Covid-19 or for other reasons.

“I don’t think that we fixed the problem, but we are part of the solution,” said Jeremiah Hough, a vice president at the barrel manufacturer.

Hough is also vice president of the Lebanon School Board. So he is keenly aware of the challenges the district faces. In September, coronavirus cases began climbing in Lebanon’s home county in southern Missouri, and continued to escalate in the following months. By early February, Laclede County had recorded 2,884 cases and 64 deaths, and one in 12 of the county’s 36,000 residents had been infected.

Hough proposed offering substitute teaching opportunities to his company’s administrative employees in December, after school administrators warned that the district was close to sending all of its roughly 4,300 students home to learn on virtual platforms because too many teachers were either sick or quarantined.

“We knew there was a risk that employees might be exposed and have to quarantine,” Hough said. “But it was a risk we were willing to try and it’s worked really well.”

The support from the local business provided a morale boost and good publicity, said David Schmitz, the Lebanon School District’s superintendent. “It’s been remarkable in helping us get the message out that we need help,” he said.

Almost no one thinks that a heavy reliance on substitutes — who usually have no teacher certification and minimal classroom experience — is ideal for students. But by getting substitutes from its community into classrooms in this unusual year, the district has managed, for now, to find local solutions to a problem that is confounding educators in its state and across the nation.

Many school districts report an ongoing daily struggle to put adults in front of students. They have pulled administrators out of offices and into classrooms, canceled professional development sessions and asked teachers to give up planning periods and juggle multiple classes. When all else has failed, they’ve sent students home to virtual learning.

The pandemic has exposed chronic staffing shortages in the country’s schools. Even before the coronavirus hit, schools were able to fill only about 54 percent of some 250,000 teacher vacancies each day, according to a survey of more than 2,000 educators released early in 2020 by the EdWeek Research Center. Now, the shortages are much worse, district leaders and principals say, because the need has grown exponentially, even as the job has become more risky. Retired teachers, a group districts often tap for help, have opted not to sub and risk exposure to the virus, while parents who seek substitute jobs for part-time income have stayed home to supervise children learning online.

The desperate search for substitute teachers has led some states and school districts to lower qualifications for the people entrusted to educate and supervise America’s schoolchildren at a moment when learning losses are already stacking up.

“When there’s difficulty filling classrooms, often the reaction is, let’s lower the bar, let’s widen the gate,” said Richard Ingersoll, a professor of education and sociology at the University of Pennsylvania. “That’s disastrous to do that. Basically, you’re sacrificing qualifications because you think it’s an emergency.”

The shortages, and the way states respond to them, could have long-term consequences: Studies have documented that just 10 days of teacher absences can result in lower math and English language arts test scores for elementary students. And not all substitute teachers are equally qualified; those with training and certifications are more effective than those with minimal credentials. Research also shows that schools with high poverty rates and large numbers of Black and Latino students have the greatest difficulties finding qualified substitutes to cover classes.

When substitutes aren’t available, principals often call upon other teachers in the building to cover for absent teachers. But even that can harm learning, said Ingersoll, who studies what he calls “out of field” teaching — teachers who are assigned to subjects that do not match their education or training.

“There’s all these stopgaps that happen, that the public doesn’t know about, which quite often are detrimental to learning,” he said.

In Missouri, where the average annual teacher pay of $51,980 is among the lowest in the nation, the pandemic has worsened long-standing shortages of full-time and substitute teachers.

“We’re all seeing the cracks that have been in the foundation for several years,” said Todd Fuller, director of marketing and communication for Missouri State Teachers Association. “We have been able to patch over the cracks, but you start to see the serious issues when you have a pandemic.”

Brent Snyder, principal of Lebanon Middle School, remembers the early months of this school year as a frantic, unhappy time.

“We would be short several staff positions every single day,” he said. “My secretary would spend the entire day calling different teachers on their plan periods to ask them to go cover a classroom. We would have classrooms that would literally have a different teacher every period of the day.”

Students lost out on instruction time, as teachers used the first 15 minutes or so of each period figuring out what was going on in the class. Kids were falling behind and teachers were in despair

“I would walk around the school and I could see the stress on their faces,” Snyder said. “I’d ask how they were doing and they would just tell me, ‘I’m exhausted.’

About the same time the local barrel manufacturer stepped in to help, the district also offered a financial incentive to cast a wider net.

The Lebanon School District pays its substitutes $85 a day — about average for districts in Missouri. That’s slightly above the state’s $10.30-an-hour minimum wage, but it wasn’t much of an enticement for a job that’s already difficult, and even more so during a pandemic. In December, the school board approved a temporary $200 bonus when a substitute completes a fifth day of work.

“We wanted to provide a bonus, but we also wanted people to commit to multiple days for us,” said Schmitz, the district’s superintendent.

In a rural school district where leaders watch over every dollar, the bonuses, which are scheduled to expire on March 31, will cost the district an additional $108,000, Schmitz said. “While that is a big price tag, we believe that to support our teachers and have quality people in the classrooms it’s a worthwhile investment,” he said.

With the pay boost, substitute teachers are now asking to be assigned to the Lebanon district, administrators said. A move to districtwide virtual classes on Fridays has also relieved some pressures. “We still might have a classroom to cover every now and then, but nothing like it was before,” Snyder said.

While the Lebanon School District achieved some success with creative local measures, broader solutions to the substitute teacher crisis have been harder to find.

The main strategy states have used is simply making it easier to become a sub. At the start of this school year, the Missouri State Board of Education suspended its requirement that applicants have 60 college credits to be certified as a substitute teacher. For a six-month period scheduled to end Sunday, anyone with a high school diploma or its equivalent can substitute if they complete a 20-hour on-line training session and pass the necessary background check.

The in the suburbs of Atlanta, the Gwinnett County Public Schools district also eased its requirements for substitute teachers, as has the entire state of Arizona. But not enough people have taken advantage, despite the economic downturn and spike in unemployment. Gwinnett is finding substitutes for only about 67 percent of teacher vacancies; last year it covered nine of 10 absences, according to the Atlanta Journal-Constitution. And school districts in Arizona still report a daily scramble to staff classrooms.

In Missouri, easing the requirements hit opposition. During a public discussion, the president of the state board, Charlie Shields, worried about lowering the standards.

“For as long as I’ve been on this board, we have said that a post-secondary educational experience is important, that we believe no one should stop at high school,” said Shields, who is CEO of a hospital system in Kansas City, Missouri. “This sends the message that it’s OK to stop at high school, and I’m troubled by that.”

The Missouri National Education Association said in a letter that “any step towards reduced standards for substitutes … sets a precedent for lowering standards to solve personnel shortages rather than improving compensation and recruitment strategies.”

But some of the policy’s supporters want to make the lowered requirements for subs permanent. “I think the state will revisit it,” said Steven Sparkman, who manages the Springfield, Missouri, office of Penmac Education Staffing, which contracts with school districts in Missouri and elsewhere to recruit and schedule substitutes. “That 60-hour college credit requirement was created so long ago.”

Sparkman said he hasn’t heard complaints about the new substitute teachers who took the 20-hour training in lieu of college credits. “Some of them have received great feedback,” he said.

Emma García, who specializes in education policy for the Economic Policy Institute, said her research indicates a need for more education and training for substitutes, not less.

“I understand that you may need to adapt your criteria to the emergency,” she said. “But the only way you can really help kids catch up is to focus on the quality of the instructors. Would you want to be vaccinated by an uncredentialed, unprepared nurse? I don’t think so.”

And while the debate on the relaxed standards is likely to continue, the change hasn’t significantly boosted Missouri’s supply of substitutes.

Al Sowers, vice president of U.S. field practice operations for Kelly Education, the nation’s largest provider of substitute teachers, said his company initially saw an uptick in people signing up to become subs. But interest waned, and his challenge is still a shortage of recruits, not a surplus.

“How I would long to have too many people,” Sowers said. “It’s not the case nationally for Kelly Education and it’s certainly not the case in Missouri.”

Connecticut is another state that’s made it easier to become a sub in order to make up for pandemic teacher shortages: The state waived its bachelor’s degree requirement. Despite the waiver, Jeffrey Solan was struggling to staff classes for the 4,200 students enrolled in the Cheshire Public Schools, where he is superintendent. “Unfortunately, it wasn’t working,” Solan said.

The day before Thanksgiving, the superintendent sat down and drafted an email.

He appealed to graduates from 2017 on to apply to substitute in the district, and explained how to begin the process. “If you like kids, want to help them learn, we need you and are committed to helping you become an effective substitute teacher,” he wrote.

When Solan reported to work the following Monday, he found 35 graduates in the application pipeline. The numbers eventually reached 50.

Cheshire Public Schools sends almost 90 percent of its graduates to four-year colleges. Many of them are home this year, studying remotely or taking a semester off. Solan’s appeal quickly created a pool of energetic young people happy to serve their community with work they could schedule around online classes.

“It’s been a family reunion of sorts,” Solan said.

On a recent Monday morning, third grade teacher Michelle Earley taught math class from home while her oil tank was being replaced. Seven of her students were also at home, attending class through a video connection. Eleven students were at their desks at Norton Elementary School.

“Remote friends, you can ask me for help,” Earley said, as she assigned the students a set of problems. “In-person friends, you can ask Ms. Marini.”

Natalee Marini graduated from Cheshire Public Schools in 2017. Now she’s back substitute teaching while she applies to graduate schools.

Ms. Marini is Natalee Marini, a 2017 Cheshire School District graduate who was supervising Earley’s classroom. She graduated from college in December with a degree in English, and hoped to attend graduate school to major in education. For her, Solan’s appeal was perfect timing. She subs three to five days a week.

“I’ll get some money and some experience doing this, and the kids are so much fun to be around,” she said.

“Having the Cheshire grads is wonderful,” Earley said. “They know the vocabulary of the district and the computer programs. Some of them are my former students. It’s nice to see them again and see how successful they are, and how much they’re willing to help.”

As with the Lebanon School District, Cheshire has managed to find a creative solution in a difficult year. But questions about who should be in charge of America’s schoolchildren when their teachers are absent will outlast the pandemic.

“Districts are seeing their substitute pools in ways that they never have before,” said Shannon Holston, director of teacher policy for the National Council on Teacher Quality. “They’re seeing them as a vital part of the school workforce.”

Some districts have stepped up training for substitutes, offered bonuses for consistent work days and provided substitute teachers with district laptops, Holston said. Some are raising their pay. “I think I’ve seen more action and changes in policy at a higher and more urgent level since the pandemic,” she said.

But the council’s own research indicates that steps like these have been a low priority for school districts before now, and will be costly to put in place during a recession. Last year, the council sampled substitute requirements in the nation’s 100 largest school districts, plus the largest district in each state. Substitute pay in those 124 districts averaged $13 an hour when adjusted for regional inflation. Only 28 districts provided health benefits, mostly for long-term subs.

Jing Liu, an assistant professor in education policy at the University of Maryland, studies availability and equity issues related to substitute teachers. Liu has argued schools that serve impoverished districts need help if they’re going to attract the numbers of qualified substitutes they’ll need to re-open.

“For sub teachers, you have to think about jobs like Uber drivers and the gig economy,” he said “You have to compete with all the alternative opportunities.”

Last year’s survey by EdWeek Research Center, which was sponsored by Kelly Education, reported a median daily pay rate of $97 for substitute teachers nationwide.

“A lot of these rates were established years ago, and they haven’t changed,” said Sowers, the Kelly executive. “We continually look at the pay for our full-time teaching workforce, but the substitute pay rate stays the same. I won’t say that pay is everything, but it’s definitely a factor.”

David Schmitz, the Lebanon School District superintendent in Missouri, said the pandemic has brought a spotlight to longstanding staffing issues, and he’d like to see Missouri permanently suspend its requirement for college credits for subs.

“We’ve always had challenges getting substitutes,” Schmitz said. “I believe there are talented and gifted people out there who may not have the 60-plus hours in college. Some of the changes that we’ve experienced because of this global pandemic may be short-lived and may go away, but some of them ought to be kept.”

His argument has plenty of support among school leaders and substitute staffing agencies in Missouri. But others contend that lowering standards is the wrong way to solve the shortfalls in teacher supply and quality that have become more glaring during the pandemic, and that kids and learning will suffer in the long run.

Meanwhile, Stefanie Fernandez, the finance administrator who’s been taking time off from her job at the barrel manufacturer to help Lebanon School District meet its need for substitutes, said she was enjoying the experience — for now.

“I do it for one day a week,” she said. “I’m not sure I would like to do it five days a week for the rest of my life.”

Snyder, principal of the middle school where Fernandez substitutes, describes her work and the services of other substitute teachers as a godsend. But Snyder, who is still seeing up to a dozen teacher absences a day, longs for a time when emergency staffing won’t be a daily issue.

“One of the things that we focus on at Lebanon Middle School is relationships,” he said. “We can provide detailed sub notes and that sub can come in and deliver the lesson and monitor the kids and do everything that they’re supposed to do. But without that relational component, it’s still better to have a seated teacher in there.”